Abstract

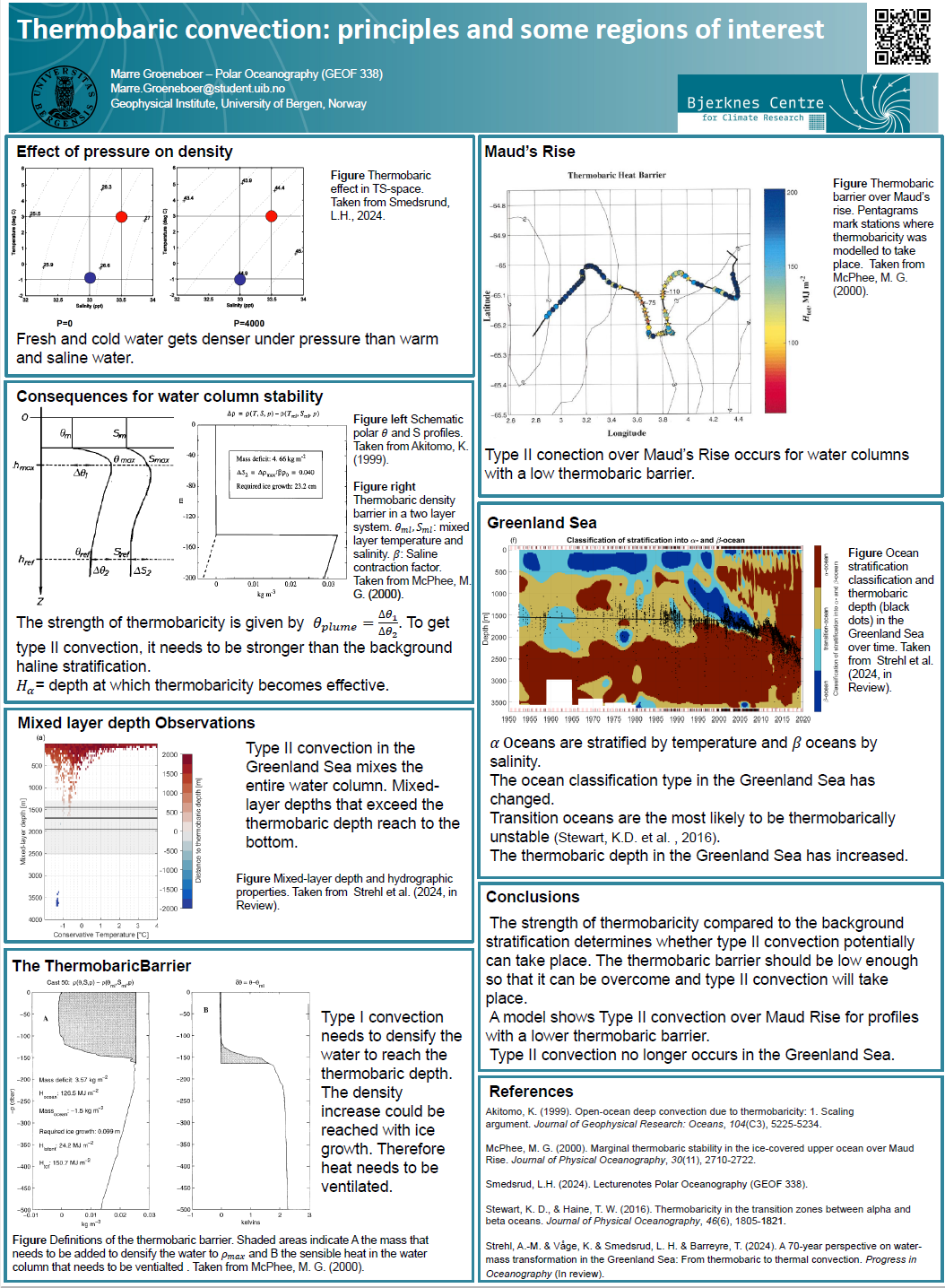

The density of water depends on temperature, salinity and pressure. When sea ice forms brine rejection takes place which leads to an increase in the density of the underlying water. Depending on the ocean stratification, this can lead to convection where the denser water sinks. This type of convection is called type I convection and occurs regularly during winter in polar seas. It slowly deepens the mixed layer as the pycnocline gets eroded. However, there is also a type II convection that can only take place under specific circumstances, and which can lead to ventilation of the entire water column. This type of convection relies on thermobaricity: the effect of pressure on water’s density. Colder, fresh waters get more compressed (and thus dense) under pressure than warm, saline waters. This means that a seemingly stable ocean profile might be unstable when a water parcel reaches a depth where thermobaricity becomes important. This can then result in type II convection. However, in order to get a type II convection, the background stratification needs to be overcome. The normalised strength of thermobaricity indicates the likeliness of this to happen. Still, there is another important factor that determines whether type II convection can occur: the thermobaric barrier. This poster dives into the processes controlling thermobaricity and examines a case study over Maud Rise near Antarctica. Lastly, it provides an overview of stratification types in the World oceans.