Abstract

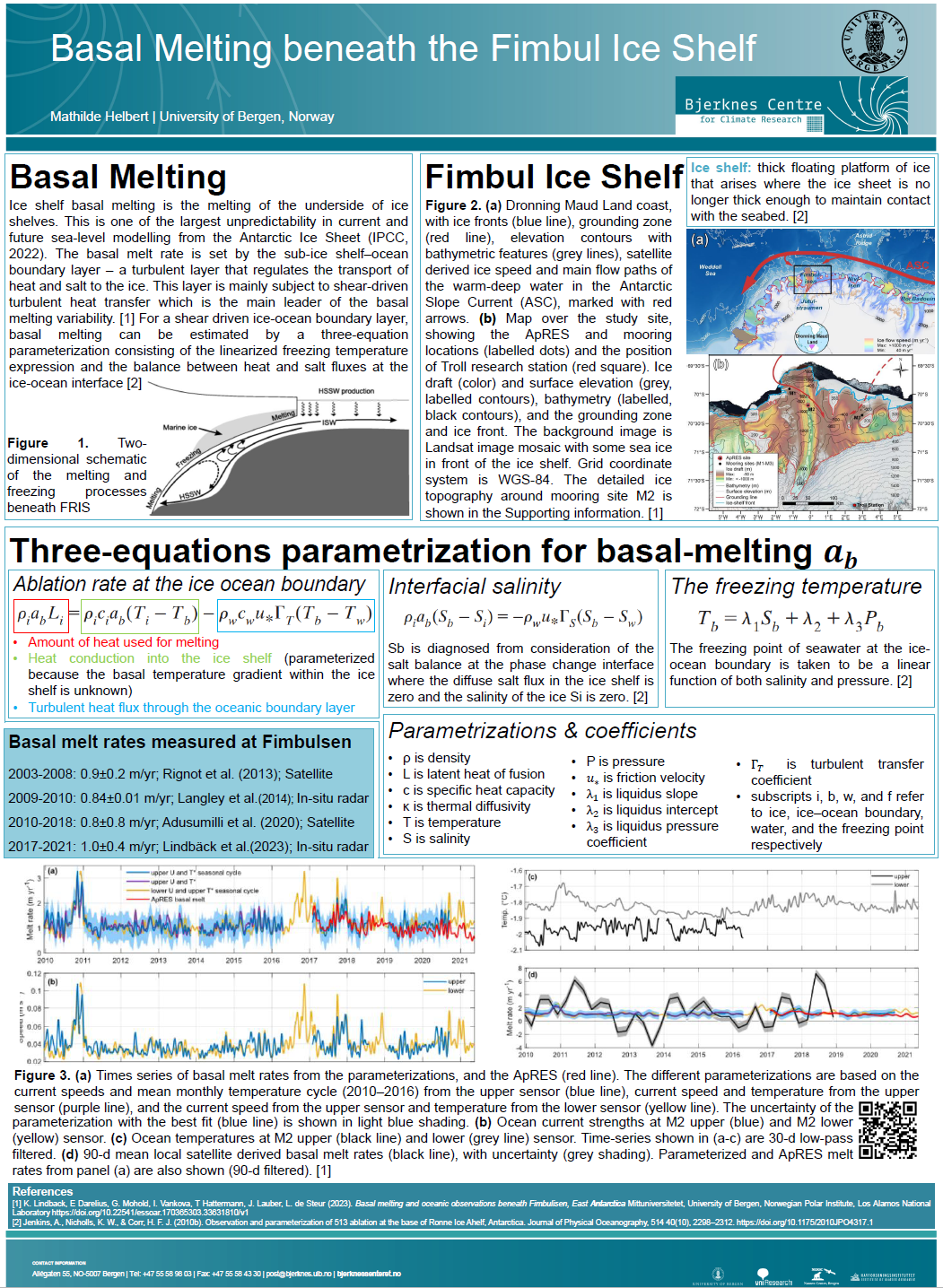

Ice shelves are thick floating platforms of ice that connect land and ocean. Since 2016, sustained warming has led to significant and increasing Antarctic basal melting - melting of the underside of ice an shelf by the ocean. The rate of basal melting is primarily influenced by the characteristics of the sub-ice shelf–ocean boundary layer, a turbulent region responsible for the exchange of heat and salt between the ocean and the ice. This turbulent layer is usually driven by convection or shear-driven processes. As ice shelves thin due to basal melting, their ability to support the ice upstream decreases, leading to an increase in the ice flow from land to sea and subsequent sea level rise. Most of the heat responsible for melting ice shelves is transported by ocean currents flowing into the cavities beneath the ice shelves. Recent observations from ApRES (Autonomous phase-sensitive Radio-Echo Sounder) at the Fimbul Ice Shelf in East Antarctica have detected a long-term mean ablation rate of up to 1.0 ± 0.4 meters per year beneath the central region of the ice shelf. Further observations from 2017 to 2021 have shown sub-weekly to monthly variations in basal melting rates attributed to shear-driven turbulent heat transfer processes along with seasonal variations driven by ocean warming during the austral summer.